We showcase the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) experimental workflow in PHIN OS™ to predict the diffusion barrier for Li-vacancy mediated diffusion along the [100] direction in LiFePO₄ (LFP). The workflow demonstrates how PHIN OS™ simplifies NEB calculations from initial/final configuration setup through transition state optimization to barrier analysis, reproducing the expected activation energy range (~0.2–0.6 eV) for this one-dimensional diffusion pathway.

Reducing the cost of energy storage is crucial for the wider adoption of renewable energy and electric vehicles. A major component of lithium-ion battery cost is the nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) cathode. Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO₄ or LFP), a leading, lower-cost alternative is slowly replacing NMC in high volume, price sensitive markets.

However, one of the primary challenges with LFP is its limited rate capability. The lower rate capability impacts the speed at which it can be charged forcing engineers to have to balance cost with performance. While nanostructuring LFP has addressed this by shortening the lithium travel distance, alternatives like chemical doping can also be used to enhance the rate capability by improving the diffusivity of LFP.

A cathode's rate capability is fundamentally linked to the active ion diffusivity and the energy barrier preventing it from moving through its host lattice. In this post, we demonstrate how the PHIN Atomic™ active learning engine can be used to predict this crucial energy barrier easily within PHIN-OS™. We achieve this by simulating the vacancy-mediated diffusion barrier of lithium along the [100] direction within the FePO₄ framework.

In LFP, lithium ions occupy the M1 sites and move through the LFP lattice through a vacancy hopping mechanism, where Li can hop into an adjacent vacant site. If there are no neighboring vacant sites, Li is immobilized until a vacancy is created around it by an adjacent Li+ moving (thus creating a vacancy). In the LiFePO₄ olivine crystal structure, these Li-vacancy pair hops occur sequentially along a chain of edge-sharing LiO6 octahedra, which are aligned parallel to a specific crystallographic axis of the lattice. This leads to fast one-dimensional transport of Li+ along the [010] or [100] channels. In contrast, diffusion is negligible in the perpendicular directions due to the lack of continuous pathways[1]. This intrinsic anisotropy means that Li+ diffusion is highly directional, where lithium ions migrate readily along the channel direction via adjacent vacancies, but cannot easily hop between parallel channels.

The energy associated with the Li+ hopping into a neighboring vacant site along the 1D chain in LiFePO₄ can be calculated with density functional theory (DFT). DFT calculations for Li-vacancy diffusion along the [100] direction report activation energies in the range of 0.2–0.6 eV [1–3]. These calculations predict high intrinsic Li diffusivity along the favored channel, around D10−8–10−7 cm2/s at room temperature.

The Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method is a technique for locating minimum-energy pathways (MEPs) and transition states between two known stable configurations[4,5]. The method discretizes the path between these states into a series of intermediate images connected by virtual springs. The springs enforce approximately uniform spacing, while the true forces from the potential energy surface relax the images toward the MEP.

The essential idea is to decompose the total force on each image into a spring component parallel to the path and a physical force component perpendicular to the path. The “nudging” prevents collapse of the band into minima and yields a proper representation of the reaction pathway.

For and image i, the total NEB force is given by:

FiNEB = Fis|| + Fi⟂

where the spring force parallel to the tangent is:

Fis|| = k(|Ri+1−Ri|−|Ri−Ri−1|)τi

and the true force perpendicular to the path is:

Fi⟂ =−∇E(Ri) − [∇E(Ri) · τi] τi

Here k is the spring constant, Ri is the configuration of image i, and τi is the unit tangent defined in the improved climb scheme by Henkelman and Jónsson’s [5].

Upon convergence, the image with the largest energy approximates the transition state. The activation barrier is obtained as the energy difference between this highest-energy image and the initial state. The climbing-image NEB [5] further refines the transition state by removing the spring force for the highest-energy image and driving it uphill along the tangent while relaxing perpendicular to the path.

PHIN OS™ provides a simple interface to configure workflows for NEB calculations. The first step is to provide the initial and final configurations of the transition state of interest. The initial and final configurations are provided directly to the NEB generator task. The NEB generator takes the initial and final configurations and interpolates between them to generate intermediate configurations.

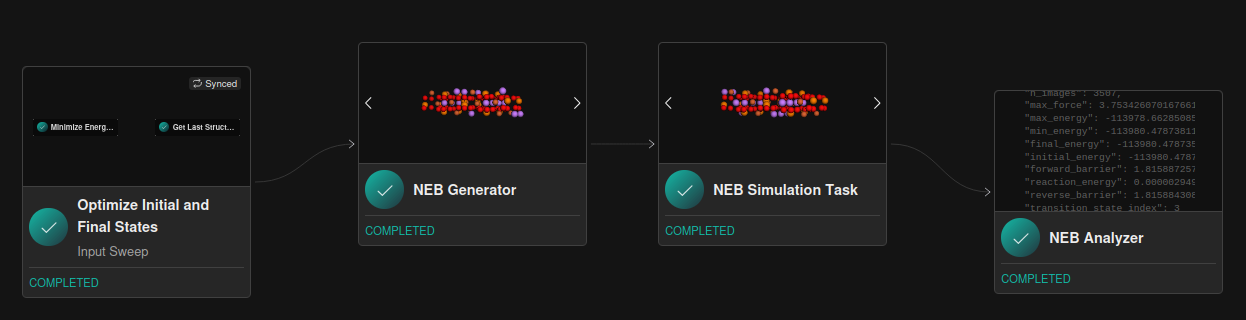

Once the NEB configurations are created, they are input into the NEB simulation task which leverages PHIN Atomic™ active learning engine to compute the NEB optimization task. This will configure the NEB simulation task and return both the optimization trajectory over each image and the final optimized transition state configuration. Finally the results from the NEB simulation task are passed to the NEB analyzer which computes the energy barriers and reaction energy. An example of the NEB workflow is shown in Figure 1.

We compare the results for Li-vacancy mediated diffusion in LiFePO4 along the [100] direction for the MACE pre-trained model and for the PHIN atomic active learning potential. The results for the symmetric barrier are shown in Table 1. The PHIN atomic migration path can be seen in the animation Figure 2. Both the MACE and PHIN Atomic predicted reaction barriers are within the range of reported DFT values (0.2–0.6 eV) for this pathway [1–3]. The initial, final, and transition state of each NEB trajectory is recalculated with DFT. The difference in the DFT benchmark barriers for MACE and PHIN Atomic is related to the slight difference in the transition state atomic configuration (i.e. bond distances and angles). For both, the DFT benchmark values are slightly lower barriers than the values computed with MACE and PHIN, although it is slightly closer for PHIN.

The PHIN OS™ NEB workflow provides a simple interface to configure and execute NEB calculations for Li-vacancy mediated diffusion in LiFePO4 along the [100] direction. The similarity of the benchmark of pre-trained (MACE) and fine-tuned (PHIN Atomic) models showcases the models are effective at calculating diffusion coefficients of materials. The PHIN OS™ platform simplifies NEB calculations given the initial final configurations through simple setup, calculation, and barrier analysis, reproducing the expected range of activation energy (~0.2–0.6 eV) for this one-dimensional diffusion pathway in LiFePO4 [1–3]. Furthermore, the workflow can easily be applied to other pathways from LFP that are doped to encourage channel-to-channel diffusion or for next generation cathode materials.

[1] D. Morgan, A. Van der Ven, G. Ceder, Li conductivity in LixMPO4 (m = mn, fe, co, ni) olivine materials, Electrochemical and Solid-State Letters 7 (2004) A30–A32. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.1633511.

[2] M.S. Islam, D.J. Driscoll, C.A.J. Fisher, P.R. Slater, Atomic-scale investigation of defects, dopants, and lithium transport in the LiFePO4 olivine-type battery material, Chemistry of Materials 17 (2005) 5085–5092. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm050999v.

[3] G.K.P. Dathar, D. Sheppard, K.J. Stevenson, G. Henkelman, Calculations of li-ion diffusion in olivine phosphates, Chemistry of Materials 23 (2011) 4032–4037. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm201604g.

[4] H. Jónsson, G. Mills, K.W. Jacobsen, Nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths of transitions, in: Classical and Quantum Dynamics in Condensed Phase Simulations, n.d.: pp. 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812839664_0016.

[5] G. Henkelman, B.P. Uberuaga, H. Jónsson, A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths, The Journal of Chemical Physics 113 (2000) 9901–9904. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1329672.