Battery simulations have traditionally required significant expertise and manual oversight to define simulation workflows and ensure accuracy. We show how both problems are addressed with PHIN-OS, a graphical interface for building and executing complex simulation workflows, and PHIN-atomic, an efficient, state-of-the-art atomic simulation engine that automates active learning of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). We leverage these tools to simulate the formation of solid electrolyte interphases, which remains a grand challenge in battery research.

The safety, longevity, and energy density of an energy storage solution is key to determining its commercial success. This is exemplified by the continuous demand for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) and their unique capability to balance all three priorities. The breakthrough that ushered lithium-ion out of the lab and into commercial operation was finding an electrolyte that formed a solid electrolyte interphase (SEI). The SEI is a passivation film that forms on the anode during manufacturing. During manufacturing, the first few battery charge/discharge cycles cause a reductive decomposition of the electrolyte protecting further decomposition. The electrolytes that were found in the 1980s were the first to form SEI’s that were stable, uniform, and ionically conductive to prevent further electrolyte breakdown, enabling efficient lithium-ion transport across the anode-electrolyte boundary, and ultimately ensuring the battery's safety and longevity. Conversely, prior electrolyte generations had poor or continually growing SEI that led to rapid capacity fade, increased internal resistance, and thermal runaway.

The invention of electrolytes that create stable SEI’s brought LIBs to mass manufacturing. Understanding the atomic-level mechanisms of SEI formation and evolution remains one of the grand challenges in battery research. Central to these electrolytes is ethylene carbonate (EC), and the formation of the SEI has been determined to be based on how EC decomposes at the anode. We aim to simulate an interface of metallic lithium (Li) and ethylene carbonate (EC), which serves as a crucial model system for SEI reactions. Through this simulation we can investigate its decomposition products, such as lithium ethylene dicarbonate (LEDC) and lithium carbonate Li2CO3, and learn how to design better electrolytes for forming SEIs.

Here we showcase simulating the formation of an SEI starting from the initial interactions and decomposition pathways of EC on a Li metal surface. We show how pairing PHIN-OS with PHIN-atomic gives researchers insights into the fundamental chemical processes that govern SEI structure and function, which are directly transferable to more complex, real-world battery chemistries.

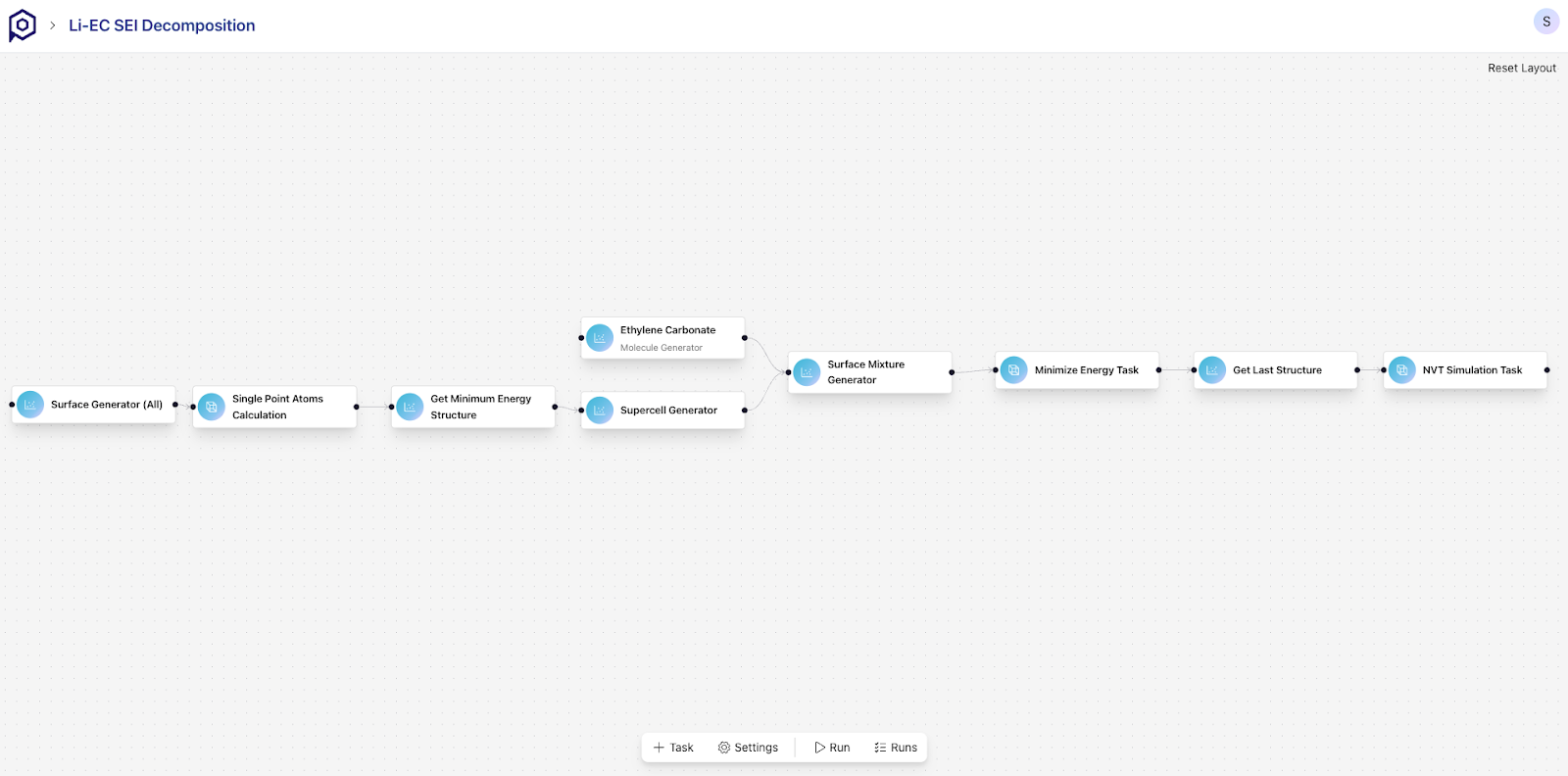

Using PHIN-OS and PHIN-atomic, we are able to set up and run electrolyte decomposition simulations quickly. The simulation workflow is seen in Figure 1. The multistep simulation workflow first finds the lowest surface energy for lithium (110) and then adds ethylene carbonate (EC) to the surface. Next the combined structure is relaxed before an NVT simulation at 300K simulates the electrolyte decomposition and SEI formation. We run two sets of simulations, the first of which uses a supercell that is tractable to calculate with density functional theory (DFT) for comparison. For this structure, we use a 2x2x2 supercell of the (110) lithium surface, adhering to the four layer minimum for surface calculations. Four EC molecules are added to the surface giving a total of 104 atoms in the structure. The second simulation extends beyond the scale of DFT simulations to model a system with larger numbers of atoms for longer timescales to gather better statistics of the interfacial reaction. The larger structure contains a 8x8x8 (110) surface of 1024 lithium atoms with 64 EC molecules on the surface leading to a total system size of 1664 atoms. The bottom layers are restricted to movement in the x-y plane to prevent drift in the non-periodic direction.

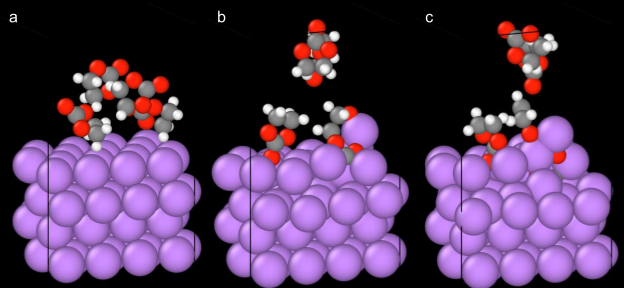

For the DFT equivalent structure, we run an NVT simulation of 1ps at 300K. The production simulation took 10 minutes to complete on our cloud infrastructure compared to an estimate of 3 months for running the equivalent simulation using ab-initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations. The significantly reduced run time, however, does not come at the cost of reduced accuracy. The fine-tuned models are trained to exactly reproduce DFT data, giving reaction pathways that correspond to previous experiments. As can be seen in Figure 2, we are able to follow the decomposition pathway to find the fundamental reaction pathways. Figure 2a shows the initial structure, Figure 2b shows one of the EC molecule undergoing a ring-opening reaction with another EC adsorbed onto the surface. Finally in 2c, the ring opening has completed with the carbonate going into the lithium subsurface to show the beginning stages of inorganic SEI formation.

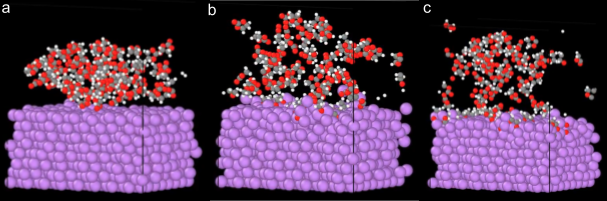

The significantly reduced cost of MLIPs allows for increasing the size of the supercell beyond DFT sizes and timescales to simulate more complex chemistry, thereby matching experimental results more closely. For the larger simulations, we run for 10ps and observe all the same processes seen in the smaller supercell, but now are able to progress the reactions further and get better statistics on the simulation results. We are able to see the formation of many different decomposition products and the formation of both organic and inorganic precursors. Many different regions of lithium carbonate are formed, resulting in the complete off gassing of ethylene gas.

Simulating the SEI formation directly remains an outstanding problem in the development of batteries and is a grand challenge due to the insight and design capability these simulations would give. Prior works have focused either on gas phase simulations of reduction to show the decomposition of EC in vacuum or use classical interatomic potentials that have been fit to reproduce examples. Neither approach is scalable. The gas phase simulations require expert interpretation for how they translate to real world environments at interfaces between solids and liquids while analytic potentials need to be fit from experimental data, leading to a chicken and egg problem. Here we show that PHIN’s fine-tuned models are able to accurately predict the decomposition products and simulate the entire formation process from 2Li + C3H4O3 => Li2CO3 + C2H4 and observe the formation of the inorganic SEI as well as off gassing. Importantly, we show this without any manual intervention and without experimental training data, showcasing the general capability of PHIN’s system to accurately predict the properties of the chemistry in battery materials.

The accurate simulation of SEI formation without manual intervention is unprecedented and paves the way for creating automated design processes that operate autonomously to suggest new electrolyte additives. These processes can design next generation stable SEI that produce batteries that are safer and easier to manufacture, ultimately reducing the price of deployed energy storage systems.